Trump Executive Order Transfers Power Back to Wall Street, Takes Away Protections from Retirement Savers

By Karla Gilbride

Cartwright-Baron Attorney

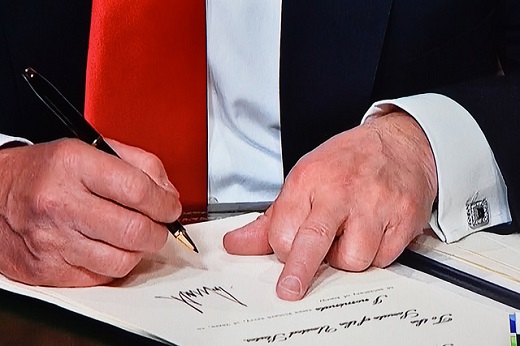

In his inaugural address, Donald Trump promised to transfer power from “the establishment” and “give it back to you, the people.” But just two weeks later, with another flourish of his very busy pen, Trump has stopped just such a transfer in its tracks.

Trump today ordered the Department of Labor to stop implementing its fiduciary rule, which was scheduled to go into effect this April.

And who asked Trump to block a rule that would have empowered investors at the expense of Wall Street? It sure wasn’t investors. Instead, big investment firms, who complain that the rule would impose new costs on them and cut into their profits, won a huge victory with Trump’s action today. And we the people lost.

The Fiduciary Rule has a simple premise: when financial advisers and securities brokers make recommendations about what we should do with our money, those recommendations should be based on what is in our best interests, not on which investment product will give the advisor the biggest commission. The rule does not prevent brokers from offering any type of product but simply requires brokers to adopt a fiduciary standard when offering advice for a fee—that is, to put the client’s best interests first—and to disclose any potential conflict of interest such as the kickbacks the broker will receive if a client rolls over her savings from one type of account into another. In other words, the rule gives investors more information so they can critically evaluate the advice they’re being given and requires investment professionals to act more like advisors and less like salespeople trying to get the best deal for themselves.

The Fiduciary Rule also empowers investors by giving them the ability to sue, either under the terms of their contracts with their brokerage firms or under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) if brokers do not act in their best interests. And while firms can require that those suits go forward in private arbitration rather than in court if they are brought by just one investor, the rule forbids brokerage firms from banning class actions in their contracts with investors if those firms want to continue recommending that investors switch to accounts for which the brokers will be compensated, the so-called “Best Interests Contract Exemption”. This is an important protection and gives investors the power to band together and hold Wall Street firms accountable for widespread abuses (though they can’t use this tool just because they’re unhappy with how an investment turned out).

The need for the Fiduciary Rule has grown as the landscape of retirement planning has changed dramatically over the last few decades, with most employers that offer retirement benefits moving from traditional pension funds into so-called defined contribution plans like 401(k)s where employees have more say over where their money is invested. (As of 2014, over 88 million Americans were enrolled in a 401(k) or other defined contribution plan.) Over this same time period, new types of retirement savings accounts like IRAs and annuities have proliferated, offering more choices but also leading to uncertainty and confusion. Many investors don’t have the time to master an alphabet soup of financial products and just want to know that if they continue to put aside some money while working, that money will grow at a reasonable rate and give them something to live on when they retire.

Enter expert financial advisers, who most people assume will navigate the complexities of the system for them and give them advice they can trust based on their personal circumstances. And no doubt many, maybe even most, financial advisors do take that trust seriously and give their clients the best advice they can, regardless of other incentives. But a number of studies summarized in a 2009 report from the Council of Economic Advisors concluded that this is not always the case. The report found that every year, retirement savers lose an average of $17 billion because brokers and financial advisors make recommendations or investment decisions that are in their own interests rather than the interests of the people whose money they are managing. For example, a broker might recommend a particular mutual fund even though it has higher fees and thus will net a lower return on investment than other options because the broker’s commission for enrolling someone in that fund is higher.

Prior to the Fiduciary Rule’s enactment in April of 2016, there was nothing preventing brokers from engaging in, and profiting from, such “conflicted compensation” arrangements. Even under the rule, such kickbacks and commissions are not outlawed, but brokers must disclose any potential conflicts of interest to their clients and explain how they are being compensated so clients can factor this information into their decisions about whether to follow the recommendation.

This rule was initially proposed in 2010 and went through two rounds of public comment, with the Department of Labor first withdrawing the rule and then proposing a new version in 2015 in response to industry concerns. Wall Street has certainly had their say in this process, but the DOL went forward with finalizing the rule last year, explaining that the long process was aimed at “balancing the need to better protect retirement savings while minimizing disruptions to the many good practices and good advice that the industry provides.” Advocacy groups for consumers, from Consumer Federation of America to the AARP, universally praised the rule, pointing out that as Americans confronting stagnant wages and increasing costs of living find it harder and harder to save for retirement, it’s especially important that they receive honest advice they can trust from those with financial and investment expertise.

In short, after extensive study and several years of negotiations, the Fiduciary Rule established important new protections for ordinary Americans planning for retirement. Now, with Donald Trump in office to do their bidding, wealthy corporate interests have delayed it from going into effect, and may try to repeal it completely. So much for “power to the people.”